When Report for America announced last week that it was placing 250 journalists into 164 local newsrooms, the list of beats they’d be covering didn’t seem too out of the ordinary. It served as a sort of non-comprehensive to-cover list for local news: climate change’s impacts on a community, rural healthcare, housing struggles, immigrant issues, the effects of population loss, “political dysfunction in suburban towns.” Good but pretty standard stuff.

Then there’s this one, from Charlotte’s public radio station WFAE, the local Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, and the Digital Public Library of America: a “unique partnership using both radio and Wikipedia to fill news deserts.”

What?

“Our missions are designed around equipping the community to make decisions about their lives,” said Ju-Don Marshall, WFAE’s chief content officer (and a former Nieman Fellow). “Ours comes from the news and information lens, and theirs [at the library] come from the information and reference lens. It makes sense to do something different and do it together.”

The entire collaboration involves two positions and three partners. WFAE will house a traditional journalist focusing on local government coverage. That person, though, will work with a second RFA participant with the title of “community Wikipedia editor,” who’ll be based a few days a week in the city’s local public library’s branches. That person will focus on researching and writing up under-covered topics from the library’s archives for Wikipedia articles — in particular those that are relevant to the Charlotte area.

The Digital Public Library of America — a six-year-old project aimed at sharing public access to the richest resources of libraries online — will assist the Wikipedia editor and help develop community engagement strategies through the work of their new data fellow, Dominic Byrd-McDevitt. He’s been a Wikipedia editor since 2004 and was previously at the National Archives and Records Administration.

It’s a way of thinking of news deserts vertically — digging into ideas and projects that aren’t usually surfaced by regular coverage — rather than horizontally across geographic space. It’s not just: “What places have no remaining local news?” It’s also: “What’s missed by the local news outlets in a place that still has them?”

‘We know that Wikipedia is one of the most successful info sources on the planet. We know that if we’d go look at the impeachment hearings article, we know that dozens if not hundreds of people have gone over that and had discussions and make it solid,” said John Bracken, the executive director of the Digital Public Library and the former vice president of technology innovation at the Knight Foundation. (The executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation, Katherine Maher, is on the DPLA board.) “We haven’t seen that Wikipedia magic applied on a sustained level in a local context, especially local communities that have been underrepresented both in journalism and Wikipedia.”

(Indeed, the Wikipedia page on the Trump impeachment inquiry has, at this writing, been edited 2,671 times by 425 different editors. And viewed 1.778 million times.)

“Being able to create the evergreen content in conjunction with the more traditional hyperlocal stories was really exciting to us, because it allows us to connect our community with the info they need, which is the mission of the library,” said Martha Yesowitch, the Charlotte Mecklenburg library’s community partnerships leader.

While this isn’t the first time that libraries and newsrooms have collaborated, it’s the first time that Report for America — to the best of cofounder Steven Waldman’s knowledge — has funded a position at a non-journalistic entity. This person’s work will be subjected to the Wikipedia editing process (which DPLA will help guide them through).

“If you look at the community in terms of the info-needs community, not in terms of the journalism needs, what are the ways in which a community gets it civically important info? The honest answer is that important players are Wikipedia and the library,” said Waldman, who back in 2011 wrote a key FCC report on “the information needs of communities.” “We’re not saying we’ll have Wikipedia volunteers — that’s where we say we need professional journalists to do the reporting where there are reporting gaps.”

Because the participants still have to selected and then trained, the exact details of these positions could shift over the next six months before they officially join for a year through RFA. (There’s a possibility of extension, as with other RFA positions.) The exact funding breakdown among the partners and the deliverables for the nontraditional role are still getting sorted out, those involved told me.

But the topics that Charlotte is seeking answers to aren’t likely to change. Marshall said that many of the questions posed to WFAE’s engagement initiative, FAQ City, show consistent confusion from residents over how the local government works: “the role of the different officials in town, what does the mayor’s office do, what is it responsible for, what are the limits of power versus the city manager, who is currently elected to the city council,” she said. “In some way it’s getting back to the basics of what local journalism used to do.”

“If you look at Wikipedia, there is an entry for Vi Lyles, the first African-American woman mayor of Charlotte, but a lot of the other city and county officials don’t have information on Wikipedia,” Yesowitch said. “I envision that the Wikipedia editor will work really closely with the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, a repository of documents and artifacts from North Carolina history, and really be able to go in and…give that context of how Charlotte has grown and developed.”

Some of the archives in the Robinson-Spangler Carolina room. Photo taken by Sarah Goldstein

This person, embedded a few days a week in different Charlotte libraries and some days in the WFAE newsroom, will also be expected to get to know the community (if they don’t already) in order to become more familiar with the questions they should be answering. And that’s another question people often raise around Report for America: Why hire a green and limited-term reporter who might not be rooted in the local culture and context?

“We attempted to go after RFA to really let us experiment in new ways of engaging our communities,” said Marshall, who worked with Waldman at his Beliefnet and LifePosts ventures. “What they’ve really done for us is give us runway to do experimentation around local news much faster than we would’ve gotten to organically for ourselves.”

WFAE has a second RFA project lined up with Charlotte’s Spanish-language newspaper La Noticia to cover immigration and deportation that also kicks off in June. In the meantime, WFAE, Report for America, the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, and the Digital Public Library of America have a lot of questions of their own to answer as these roles get ironed out.

“One of the things exciting about this experiment is that, if it works well, it’s replicable in every community in the country that has a library, Wikipedia pages, and a journalistic entity,” Waldman said. “It could become a model that could spread across the country and scale in a dramatic way that could make a big dent on the gaps of information.”

Editor’s note: Our friend Danna Young is a scholar of, among other things, the intersection of entertainment and information — particularly humor’s use within the political landscape and the ways in which its messages reach and affect audiences.

She has a terrific new book out this week from Oxford University Press: Irony and Outrage: The Polarized Landscape of Rage, Fear, and Laughter in the United States. In this piece, she describes how conservative and liberal media differ not only in content, but also in form — in ways that exacerbate polarization.

1996 was a banner year for America’s polarized media ecosystem.

In October, a new 24-hour news channel was introduced to American audiences. “I figure there are 18 shows for freaks,” the former Republican strategist and Rush Limbaugh producer Roger Ailes told the Associated Press in 1995. “If there’s one network for normal people it’ll balance out.” As CEO of the new Fox News Channel, working alongside founder Rupert Murdoch, Ailes would have his chance to create that “network for normal people,” packed with analysis and opinion programming, with a dash of news for good measure. Among those “analysis and opinion shows” was The O’Reilly Report (later rebranded as The O’Reilly Factor), a conservative opinion talk show hosted by former Inside Edition entertainment talk show host Bill O’Reilly.

From its inception, The Factor defined the conservative television talk genre. It also exemplified a genre that Tufts University’s Jeffrey Berry and Sarah Sobieraj refer to as “outrage.”

But what some people may have missed is that just three months earlier, in July 1996, another non-traditional form of news-ish programming launched — also as a response to mainstream media. It was a news parody and satire program called The Daily Show, on Comedy Central. Created by Lizz Winstead and Madeleine Smithberg, The Daily Show featured headlines from the day’s pop culture news and introduced fictional news correspondents in pretend “field segments.”

Winstead and Smithberg set out to create a parody program that commented, not just on the politics of the day, but also on the emerging cable news landscape that “produced” politics as entertainment. In an interview with The Cut, Winstead recalled sitting in a bar, watching Gulf War coverage on CNN: “We were all watching the Gulf War unfold and it felt like we were watching a made-for-TV show about the war. It changed my comedy — I started writing about how we are served by the media.” Their framing from the start: “to do a news satire where the genre itself was a character in the show.”

The twin births of The Daily Show and The O’Reilly Factor in 1996 were not a coincidence. Both programs were the result of changes in the economic and regulatory underpinnings of the media industry and the development of new cable and digital technologies. Both presented politically relevant information that offered an alternative (in form and function) to mainstream news. Both were reactions to a news environment being transformed by pressures stemming from media deregulation throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Both were positioned as reactions to problematic aspects of mainstream journalism. Both tapped into an increasingly polarized political electorate. And both reflected the economics of media fragmentation that replaced large, heterogeneous, mass audiences with small, homogenous, niche audiences — homogeneous in demographic, psychographic, and even political characteristics.

When scholars and journalists discuss conservative outlets like Fox News, they typically position the cable network MSNBC as its closest functional equivalent on the left. While it’s fair to say that the MSNBC of 2019 is a liberal-leaning cable news outlet that features liberal political analysis programming, this iteration of the network is relatively recent. When MSNBC was introduced in 1996, the network featured talk shows and news analysis shows from across the political spectrum. In fact, several conservative political talk personalities (including Tucker Carlson, Laura Ingraham, and Ann Coulter) started their cable news careers at MSNBC. It wasn’t until the mid-2000s that the network, failing in the ratings war, pivoted to the left and positioned itself as a liberal alternative to Fox.

But from the moment The Daily Show launched during that fateful summer of 1996, it did reflect an overwhelming liberal ideology. I’m not referring to its targets or political point of view — I’m referring to the ideological leaning of the packaging and aesthetics of satire: packaging and aesthetics that run counter to those of conservative opinion talk.

That’s right: What if satire actually has a liberal bias, not due to its targets and arguments, but due to its playful aesthetic, layered and ironic rhetorical structures, and rampant self-deprecation? And what if political talk actually has a conservative bias, not due to its targets and arguments, but due to its constant threat-monitoring, didactic rhetorical structures, and moral seriousness?

Yes, the content, effects, and aesthetics of liberal satire and conservative opinion talk are completely different. So it can seem counterintuitive to conceptualize satire as any kind of liberal equivalent to conservative opinion talk. But we know that the two genres serve parallel functions for their audiences: highlighting important issues and events, setting their audiences’ agendas, framing the terms of debate, informing them on ideologically resonant issues, and even mobilizing them. And we know that the audiences of both liberal satire and conservative outrage show low trust in news, low trust in institutions, and enormous political efficacy (meaning confidence that they are equipped to participate politically). And both showed up in America’s living rooms within three months of each other in 1996 — each framed as a response to problematic aspects of television news.

In my book Irony and Outrage, I argue that the modern birth of these genres can be traced to the same set of political and technological changes in the political and news ecosystem in the 1980s and 1990s. I also argue that the distinct look and feel of these genres can be traced to underlying differences in the psychological profiles of people on the left and the right — differences that shape how we orient to the worlds around us and the kinds of content we are most likely to create and consume.

In my book Irony and Outrage, I argue that the modern birth of these genres can be traced to the same set of political and technological changes in the political and news ecosystem in the 1980s and 1990s. I also argue that the distinct look and feel of these genres can be traced to underlying differences in the psychological profiles of people on the left and the right — differences that shape how we orient to the worlds around us and the kinds of content we are most likely to create and consume.

Decades of research from political psychology points to important psychological and physiological differences between liberals and conservatives that hinge on how we monitor our environments for — and engage with — threat. Conservatives, who are more prone to threat monitoring, have a lower tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity — a trait that correlates with various lifestyle, occupational, and even artistic preferences. Liberals, who are less cognizant of threats in their environments, are less likely than conservatives to rely on emotional shortcuts or heuristics, instead thinking more carefully and evaluating information as it comes in.

Conservatives (especially social and cultural conservatives) tend to value efficiency and clarity. They prefer order, boundaries, and instinct. I find that that these inclinations shape their political information preferences — preferences for didactic, morally serious, threat-oriented content that leaves very little doubt about what viewers should be worried about and who is to blame. Content like we find on Hannity or The Ingraham Angle.

Liberals, on the other hand, are more comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. With a lower threat salience, they are more open to play and experimentation. These inclinations shape their political information preferences — for layered, ironic, complex arguments that often never really say exactly what they mean. Content like we find on The Daily Show or Last Week Tonight with John Oliver.

While these genres have shared roots and may even serve parallel purposes for their viewers, the symbiotic relationship between each side’s preferred aesthetic and the psychology of their viewers renders their impact quite asymmetrical.

The underlying logic and aesthetic of conservative outrage make it an ideal mechanism for tactical, goal-driven political mobilization. With its use of emotional language and focus on threats, it constitutes what philosopher Jacques Ellul refers to as “agitation propaganda.” Writing in 1962, Ellul described “hate” as the most profitable resource of agitation propaganda:

It is extremely easy to launch a revolutionary movement based on hatred of a particular enemy. Hatred is probably the most spontaneous and common sentiment; it consists of attributing one’s misfortunes and sins to “another”…

Importantly, it is not only the content of conservative outrage that renders it powerful. Rather, it’s the symbiosis between the threat-oriented content and the unique psychology of the conservative audience that facilitates its political impact. These conservative audience members, psychologically oriented towards protection and the maintenance of a stable society, are poised to respond to the people, groups, and institutions that have been identified as threats. The fact that these are the very characteristics of outrage content that have been harnessed by the conservative wing of the Republican Party should not come as a surprise.

In contrast, satire is a genre that remains in a state of play, downplays its own moral certainty and issues judgments through implication rather than proclamation. As a result, liberal political elites’ ability to harness satire and use it to their own ends is compromised. While the symbiosis between outrage and conservatism lends itself to strategic persuasion and mobilization, the symbiosis between the aesthetic of irony and the underlying psychology of liberalism render satire fruitful as a forum for exploration and rumination, but not for mobilization.

Consider one of the most critically acclaimed and influential pieces of satire of the past decade: Colbert’s 2011 creation of an actual super PAC, Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow.

Colbert’s coverage of super PACs and Citizens United influenced public opinion and knowledge of the topic. But, according to Colbert, he didn’t create his super PAC with political or persuasive intentions at all. He didn’t push the limits of campaign finance in an effort to fuel activism on the issue of campaign finance reform. Rather, the whole thing came about by accident.

After having mentioned a fictional super PAC at the end of a political parody on The Colbert Report, Comedy Central expressed resistance to the idea of an actual Colbert super PAC. “Are you really going to get a PAC?” a network representative asked Colbert. “Because if you actually get a PAC, that could be trouble.” To which Colbert replied: “Well, then, I’m definitely doing to do it.”

And so began the largely organic and experimental process of launching and raising funds for an actual super PAC and learning about the (nearly nonexistent) limits of campaign financing. As Colbert explained: “[At] every stage of it, I didn’t know what was going to happen next. It was just an act of discovery. It was purely improvisational. And, you know, people would say, ‘What is your plan?’ My plan is to see what I can and cannot do with it.”

When The Daily Show and Fox News both appeared in 1996, it would have seemed ridiculous to suggest they had much in common. But I say that they do, especially in terms of the technological, political, journalistic, and regulatory changes that gave rise to both. Ironic satire and political outrage programming look and feel different because of the unique values, needs, and aesthetic preferences of the kinds of people who create and consume each one. But the potential for these two genres to be used strategically towards partisan mobilization is absolutely not the same.

If outrage is a well-trained attack dog that operates on command, satire is a raccoon — hard to domesticate and capable of turning on anyone at any time.

Does satire have a liberal bias? Sure. Satire has a liberal psychological bias. But the only person who can successfully harness the power of satire is the satirist. Not political strategists. Not a political party. Not a presidential candidate. Outrage is the tool of conservative elites. But ironic satire is the tool of the liberal satirist alone.

Dannagal Goldthwaite Young is an associate professor of communication at the University of Delaware and author of Irony and Outrage: The Polarized Landscape of Rage, Fear, and Laughter in the United States.

Sabrina Orah Mark’s monthly column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

“I hope you’re not afraid of mice,” my friend Amy says. I am in her car. She clicks open the glove box and a soft shock of fur and paper and string gently exhales. A mouse nest. “Hello there,” says Amy. The nest is mouse-less for now, but the mice will return to it when it gets cold. Eventually the mice will eat the guts of the car, a mechanic told her. But Amy won’t disturb the nest. “It’s their home,” she says, shutting the glove box back up, but not before petting the little nest that seems so alive I swear it might be breathing.

For years I have kept Rene Magritte’s “The Healer” over my writing desk. The bronze man with an open birdcage for a chest. A cane in one hand, and a suitcase in the other. Limp and flee, limp and flee, limp and flee. He is faceless, and his cloak is open. There’s a hat on his nowhere head, and in place of his heart is a nook for doves to rest. Amy’s car moves me like “The Healer” moves me. Both tell a story of kindness and protection and ruin. Both will give up their guts to keep the vulnerable ones safe. Months later, I am again in Amy’s car. The nest has doubled in size. The car, for now, still runs perfectly.

Fairytales are crowded with saviors: the prince on his horse, fairies, gnomes, godmothers, and witches. They appear out of nowhere. They are hidden, like the subterranean and the aristocratic, and then out of a clearing they arrive to save, or erase, or enchant the day. They are not angels or saints. And they are not without flaws. In German, Rumpelstiltskin (or Rumpelstilzchen) means little rattle ghost. And it is Rumpelstiltslkin who can, unlike the miller’s daughter, spin straw into gold. He saves her, and even adds an escape clause to their contract because he a compassionate gnome: If she guesses his name in three days she can keep her child. He spins like the storyteller spins. And as he spins I wonder if the miller’s daughter ever hears the whir, whir, whir in his empty chest. For his work, he wants what is missing. He wants something alive. No, the miller’s daughter cannot hear the whir. She has cried herself soundly to sleep.

“I prefer a living creature,” says Rumpelstiltskin, “to all the treasures in the world.”

I wonder sometimes what The Healer would do if there were no doves. Would The Healer still exist if he was empty of the thing he was trying to save? Would he stand up and walk home? Would he disappear entirely? Would his ancient face slowly return?

In Italian, Rumpelstiltskin is Tremotino, which means “Little Earthquake.” “All great storytellers,” writes Walter Benjamin, “have in common the freedom with which they move up and down the rungs of their experience as on a ladder. A ladder extending downward to the interior of the earth and disappearing into the clouds…” Gnomes also come from the interior, and can move through solid earth as easily as humans can move through air. When I write I am rumple, and stilt, and skin. Everything is in disarray, and then if I’m lucky there’s an ascension, and then an undress. Lately I have been hurting people I love with my writing. One friend (who is now no longer my friend), whose name I used in a story which was not about her, said to me, “I need to protect myself as a human being,” as if the story I wrote asked for a living part of her. I wasn’t the healer’s chest or the glove box like I had always hoped to be. I had always believed writing kept oblivion at bay, but suddenly I was accused of spinning it into a thicker existence. My fiction punctured my reality, and now I was the rattle ghost that disrupted my friend’s kingdom. “Tomorrow I brew, today I bake, / Soon the child is mine to take.” Her name is not Rumpelstiltskin, though she did once teach me how to spin straw into gold. She once taught me how to write, and in return I hurt her. Her name means enclosure. Like a nest or a cage.

“The storyteller,” writes Walter Benjamin, “is the man who could let the wick of his life be consumed completely by the gentle flame of his story.”

Once, many years ago, when I was only writing poems, an ex-boyfriend gave me a mannequin head for my birthday. It was rescued, he told me, from a children’s clothing shop that had caught fire. The head was a boy’s head. With singed hair and ash marks across its face. On the night he gave it to me, he told me he had fallen in love with someone else. I remember carrying the head home. I took the subway with it on my lap too sad to realize what a sight we were. For about a year, I tried to keep the head in my apartment. It had already been through so much, and I couldn’t bear the thought of throwing something away with eyes and a mouth. But it ate at me, this boy’s head. It was hungry for something that hurt. It stared at me. I wrapped it in an old, soft blanket, and moved it to the back of my closet. Finally I brought it to the Salvation Army and left it there. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I just can’t,” I said.

How much of what I try to rescue is not actually the broken thing in my hands, but the broken thing inside myself? The burnt lonely boy, and the girl with no magic, and the doves and the mice. When I write I spin a long, knotted rope. I toss the rope down. And it is me who is climbing up, and it is me who is climbing down.

A miller is also a moth with powdery wings. Moths cannot tell the difference between artificial light and moonlight. It’s not the miller’s daughter’s fault she cannot spin. It’s her father’s fault. He trapped her, “in order to appear as a person of some importance.” And she’s only a moth girl with powdery wings. A nameless moth only two letters away from being a mother. Two letters and a name.

I have a dream in which Amy pulls the whole nest out of the glove box and tells me we should eat it. She holds it up like it’s a soft piece of cake. “I’m sorry,” I say. “I just can’t,” I say. “I have no more room.” “But it’s your birthday,” says Amy. “And you forgot to blow out all the candles and make a wish. And now nothing will come true.”

My sons play this trick on their friends. It goes like this: “I one my mother.” And then the friend goes, “ I two my mother.” And then back and forth: “I three my mother, I four my mother, I five my mother, I six my mother, I seven my mother, I eight my mother.” And then my sons say, “oh my god you ate your mother!” And everybody laughs. Because the mother inside the body of her child cracks everybody up. A crack like a fault line that shakes the earth. And down, down, down goes the mother into the body of her son. Where finally she can rest. And feel safe. I’d be less afraid of dying if I knew I could one day be buried in the bodies of my sons. I know this sounds grim, but it’s true.

Rumpelstiltskin dates back to the 16th century, and can be traced back to Johann Fischart’s Affentheurlich Naupengeheurliche Geschichtklitterung (1577), which very roughly translates to Glorious Storytelling. In it Fischart describes a game called Rumpele stilt oder der Poppart (or Noise, Limp, Goblin), which is like Duck, Duck, Goose except instead of a goose there’s a goblin, and instead of a duck there’s a man with a limp. The children take turns chasing after each other like goblins, and scaring each other away with goblinish sounds. The objective of the game, like so many games, is for the children to save themselves.

As a kid in Yeshiva, I remember singing about the messiah. Hundreds of kids jumping and shouting. Our red cheeks glowed with a desire for a desire we were taught to desire: “We want Moshiach now. We want Moshiach now. We want Moshiach now. We don’t want to wait.” But I didn’t want Moshiach now. Even at seven I knew the only thing more traumatic than the Messiah never coming, was the Messiah actually showing up. I had a hunch the coming of the Messiah meant losing something. But I couldn’t imagine what. Now I know what I was afraid to lose was control of the spindle. I was terrified of being saved by a story that wrote me before I could even begin to write it.

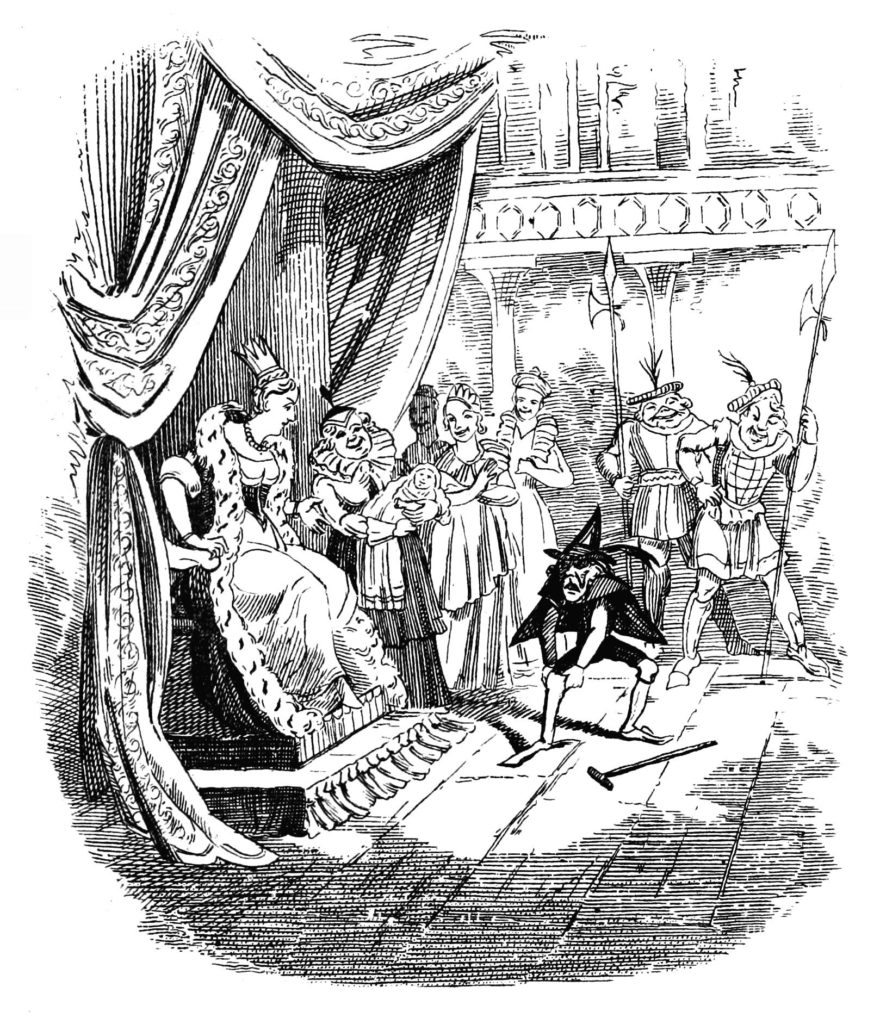

There is a drawing of Rumpelstiltskin (by George Cruikshank) where he looks like the 27th letter of the alphabet. A letter that should’ve come after Z, but fell behind. When the miller’s daughter tells Rumpelstiltskin she knows his name, he stomps his right leg so hard so hard it goes into the earth. His lines are sharp like thunderbolts. He looks like a dying letter, or an animal going extinct. The nameless queen and her nameless courtiers are standing around him laughing and laughing. Even the nameless baby appears to be laughing. Half buried, Rumpelstiltskin rips himself in two.

What becomes of Rumpelstiltskin? In Kevin Brockmeier’s “A Day in the Life of Half of Rumpelstiltskin,” half of Rumpelstiltskin dreams he unspins himself at the wheel:

“When the last of him whisks from the treadle and into the air, he is gold, through and through. He lies there perfect, glinting, and altogether gone. Half of Rumpelstiltskin is the whole of the picture and nowhere in it. He is beautiful, and remunerative, and he isn’t even there to see it. Half of Rumpelstiltskin has spun himself empty. There is nothing of him left.”

By saving the girl, Rumpelstiltskin fell apart. But what good is his magic if it goes unused? I sit in the passenger seat of Amy’s car, knowing one day the car will stop running. And the mice will stop nibbling. And these words will fade like the marks on the burnt boy’s head. All of us are the whole of the picture, and all of us are nowhere in it. Our magic is also our undoing.

Rumpelhealskin, Rumpelprayskin, Rumpelpoemskin, Rumpelloveskin, Rumpelsaveskin. Rumpelsonskin, RumpelAmyskin, Rumpelstoryskin, Rumpeltruthskin, Rumpelpainskin. I used to think being a writer meant being a kind of guardian, a good guy. Maybe that was when I had enough of me to spare Now I know better. It’s about always being torn in half. It’s about being dead and alive. An asylum and a danger. A rattle and a lullaby. Mother and unmother. Saved and forgotten. A feral angel. A wing and a paw. Broken and sutured. I’m sorry. You’re sorry. You hurt me. I fixed you. I lost you. You found me.

Read earlier installments of Sabrina Orah Mark’s monthly column, Happily, here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

Ten days after I called off my engagement I was supposed to go on a scientific expedition to study the whooping crane on the gulf coast of Texas. Surely, I will cancel this trip, I thought, as I shopped for nylon hiking pants that zipped off at the knee. Surely, a person who calls off a wedding is meant to be sitting sadly at home, reflecting on the enormity of what has transpired and not doing whatever it is I am about to be doing that requires a pair of plastic clogs with drainage holes. Surely, I thought, as I tried on a very large and floppy hat featuring a pull cord that fastened beneath my chin, it would be wrong to even be wearing a hat that looks like this when something in my life has gone so terribly wrong.

Ten days earlier I had cried and I had yelled and I had packed up my dog and driven away from the upstate New York house with two willow trees I had bought with my fiancé.

Ten days later and I didn’t want to do anything I was supposed to do.

*

I went to Texas to study the whooping crane because I was researching a novel. In my novel there were biologists doing field research about birds and I had no idea what field research actually looked like and so the scientists in my novel draft did things like shuffle around great stacks of papers and frown. The good people of the Earthwatch organization assured me I was welcome on the trip and would get to participate in “real science” during my time on the gulf. But as I waited to be picked up by my team in Corpus Christi, I was nervous—I imagined everyone else would be a scientist or a birder and have daunting binoculars.

The biologist running the trip rolled up in in a large white van with a boat hitch and the words BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES stenciled across the side. Jeff was forty-ish, and wore sunglasses and a backward baseball cap. He had a winter beard and a neon-green cast on his left arm. He’d broken his arm playing hockey with his sons a week before. The first thing Jeff said was, “We’ll head back to camp, but I hope you don’t mind we run by the liquor store first.” I felt more optimistic about my suitability for science.

*

Not long before I’d called off my engagement it was Christmas.

The woman who was supposed to be my mother-in-law was a wildly talented quilter and made stockings with Beatrix Potter characters on them for every family member. The previous Christmas she had asked me what character I wanted to be (my fiancé was Benjamin Bunny). I agonized over the decision. It felt important, like whichever character I chose would represent my role in this new family. I chose Squirrel Nutkin, a squirrel with a blazing red tail—an epic, adventuresome figure who ultimately loses his tail as the price for his daring and pride.

I arrived in Ohio that Christmas and looked to the banister to see where my squirrel had found his place. Instead, I found a mouse. A mouse in a pink dress and apron. A mouse holding a broom and dustpan, serious about sweeping. A mouse named Hunca Munca. The woman who was supposed to become my mother-in-law said, “I was going to do the squirrel but then I thought, that just isn’t CJ. This is CJ.”

What she was offering was so nice. She was so nice. I thanked her and felt ungrateful for having wanted a stocking, but not this stocking. Who was I to be choosy? To say that this nice thing she was offering wasn’t a thing I wanted?

When I looked at that mouse with her broom, I wondered which one of us was wrong about who I was.

*

The whooping crane is one of the oldest living bird species on earth. Our expedition was housed at an old fish camp on the Gulf Coast next to the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, where three hundred of the only six hundred whooping cranes left in the world spend their winters. Our trip was a data-collecting expedition to study behavior and gather data about the resources available to the cranes at Aransas.

The ladies bunkhouse was small and smelled woody and the rows of single beds were made up with quilts. Lindsay, the only other scientist, was a grad student in her early twenties from Wisconsin who loved birds so much that when she told you about them she made the shapes of their necks and beaks with her hands—a pantomime of bird life. Jan, another participant, was a retired geophysicist who had worked for oil companies and now taught high school chemistry. Jan was extremely fit and extremely tan and extremely competent. Jan was not a lifelong birder. She was a woman who had spent two years nursing her mother and her best friend through cancer. They had both recently died and she had lost herself in caring for them, she said. She wanted a week to be herself. Not a teacher or a mother or a wife. This trip was the thing she was giving herself after their passing.

At five o’clock there was a knock on the bunk door and a very old man walked in, followed by Jeff.

“Is it time for cocktail hour?” Warren asked.

Warren was an eighty-four-year-old bachelor from Minnesota. He could not do most of the physical activities required by the trip, but had been on ninety-five Earthwatch expeditions, including this one once before.Warren liked birds okay. What Warren really loved was cocktail hour.

When he came for cocktail hour that first night, his thin, silver hair was damp from the shower and he smelled of shampoo. He was wearing a fresh collared shirt and carrying a bottle of impossibly good scotch.

Jeff took in Warren and Jan and me. “This is a weird group,” Jeff said.

“I like it,” Lindsay said.

*

In the year leading up to calling off my wedding, I often cried or yelled or reasoned or pleaded with my fiancé to tell me that he loved me. To be nice to me. To notice things about how I was living.

One particular time, I had put on a favorite red dress for a wedding. I exploded from the bathroom to show him. He stared at his phone. I wanted him to tell me I looked nice, so I shimmied and squeezed his shoulders and said, “You look nice! Tell me I look nice!” He said, “I told you that you looked nice when you wore that dress last summer. It’s reasonable to assume I still think you look nice in it now.”

Another time he gave me a birthday card with a sticky note inside that said BIRTHDAY. After giving it to me, he explained that because he hadn’t written in it, the card was still in good condition. He took off the sticky and put the unblemished card into our filing cabinet.

I need you to know: I hated that I needed more than this from him. There is nothing more humiliating to me than my own desires. Nothing that makes me hate myself more than being burdensome and less than self-sufficient. I did not want to feel like the kind of nagging woman who might exist in a sit-com.

These were small things, and I told myself it was stupid to feel disappointed by them. I had arrived in my thirties believing that to need things from others made you weak. I think this is true for lots of people but I think it is especially true for women. When men desire things they are “passionate.” When they feel they have not received something they need they are “deprived,” or even “emasculated,” and given permission for all sorts of behavior. But when a woman needs she is needy. She is meant to contain within her own self everything necessary to be happy.

That I wanted someone to articulate that they loved me, that they saw me, was a personal failing and I tried to overcome it.

When I found out that he’d slept with our mutual friend a few weeks after we’d first started seeing each other, he told me we hadn’t officially been dating yet so I shouldn’t mind. I decided he was right. When I found out that he’d kissed another girl on New Year’s Eve months after that, he said that we hadn’t officially discussed monogamy yet, and so I shouldn’t mind. I decided he was right.

I asked to discuss monogamy and, in an effort to be the sort of cool girl who does not have so many inconvenient needs, I said that I didn’t need it. He said he thought we should be monogamous.

*

Here is what I learned once I began studying whooping cranes: only a small part of studying them has anything to do with the birds. Instead we counted berries. Counted crabs. Measured water salinity. Stood in the mud. Measured the speed of the wind.

It turns out, if you want to save a species, you don’t spend your time staring at the bird you want to save. You look at the things it relies on to live instead. You ask if there is enough to eat and drink. You ask if there is a safe place to sleep. Is there enough here to survive?

Wading through the muck of the Aransas Reserve I understood that every chance for food matters. Every pool of drinkable water matters. Every wolfberry dangling from a twig, in Texas, in January, matters. The difference between sustaining life and not having enough was that small.

If there were a kind of rehab for people ashamed to have needs, maybe this was it. You will go to the gulf. You will count every wolfberry. You will measure the depth of each puddle.

*

More than once I’d said to my fiancé, How am I supposed to know you love me if you’re never affectionate or say nice things or say that you love me.

He reminded me that he’d said “I love you” once or twice before. Why couldn’t I just know that he did in perpetuity?

I told him this was like us going on a hiking trip and him telling me he had water in his backpack but not ever giving it to me and then wondering why I was still thirsty.

He told me water wasn’t like love, and he was right.

There are worse things than not receiving love. There are sadder stories than this. There are species going extinct, and a planet warming. I told myself: who are you to complain, you with these frivolous extracurricular needs?

*

On the gulf, I lost myself in the work. I watched the cranes through binoculars and recorded their behavior patterns and I loved their long necks and splashes of red. The cranes looked elegant and ferocious as they contorted their bodies to preen themselves. From the outside, they did not look like a species fighting to survive.

In the mornings we made each other sandwiches and in the evenings we laughed and lent each other fresh socks. We gave each other space in the bathroom. Forgave each other for telling the same stories over and over again. We helped Warren when he had trouble walking. What I am saying is that we took care of each other. What I am saying is we took pleasure in doing so. It’s hard to confess, but the week after I called off my wedding, the week I spent dirty and tired on the gulf, I was happy.

On our way out of the reserve, we often saw wild pigs, black and pink bristly mothers and their young, scurrying through the scrub and rolling in the dust among the cacti. In the van each night, we made bets on how many wild pigs we might see on our drive home.

One night, halfway through the trip, I bet reasonably. We usually saw four, I hoped for five, but I bet three because I figured it was the most that could be expected.

Warren bet wildly, optimistically, too high.

“Twenty pigs,” Warren said. He rested his interlaced fingers on his soft chest.

We laughed and slapped the vinyl van seats at this boldness.

But the thing is, we saw twenty pigs on the drive home that night. And in the thick of our celebrations, I realized how sad it was that I’d bet so low. That I wouldn’t even let myself imagine receiving as much as I’d hoped for.

*

What I learned to do, in my relationship with my fiancé, was to survive on less. At what should have been the breaking point but wasn’t, I learned that he had cheated on me. The woman he’d been sleeping with was a friend of his I’d initially wanted to be friends with, too, but who did not seem to like me, and who he’d gaslit me into being jealous of, and then gaslit me into feeling crazy for being jealous of.

The full course of the gaslighting took a year, so by the time I truly found out what had happened, the infidelity was already a year in the past.

It was new news to me but old news to my fiancé.

Logically, he said, it doesn’t matter anymore.

It had happened a year ago. Why was I getting worked up over ancient history?

I did the mental gymnastics required.

I convinced myself that I was a logical woman who could consider this information about having been cheated on, about his not wearing a condom, and I could separate it from the current reality of our life together.

Why did I need to know that we’d been monogamous? Why did I need to have and discuss inconvenient feelings about this ancient history?

I would not be a woman who needed these things, I decided.

I would need less. And less.

I got very good at this.

*

“The Crane Wife” is a story from Japanese folklore. I found a copy in the reserve’s gift shop among the baseball caps and bumper stickers that said GIVE A WHOOP. In the story, there is a crane who tricks a man into thinking she is a woman so she can marry him. She loves him, but knows that he will not love her if she is a crane so she spends every night plucking out all of her feathers with her beak. She hopes that he will not see what she really is: a bird who must be cared for, a bird capable of flight, a creature, with creature needs. Every morning, the crane-wife is exhausted, but she is a woman again. To keep becoming a woman is so much self-erasing work. She never sleeps. She plucks out all her feathers, one by one.

*

One night on the gulf, we bought a sack of oysters off a passing fishing boat. We’d spent so long on the water that day I felt like I was still bobbing up and down in the current as I sat in my camp chair. We ate the oysters and drank. Jan took the shucking knife away from me because it kept slipping into my palm. Feral cats trolled the shucked shells and pleaded with us for scraps.

Jeff was playing with the sighting scope we used to watch the birds, and I asked, “What are you looking for in the middle of the night?” He gestured me over and when I looked through the sight the moon swam up close.

I think I was afraid that if I called off my wedding I was going to ruin myself. That doing it would disfigure the story of my life in some irredeemable way. I had experienced worse things than this, but none threatened my American understanding of a life as much as a called-off wedding did. What I understood on the other side of my decision, on the gulf, was that there was no such thing as ruining yourself. There are ways to be wounded and ways to survive those wounds, but no one can survive denying their own needs. To be a crane-wife is unsustainable.

I had never seen the moon so up-close before. What struck me most was how battered she looked. How textured and pocked by impacts. There was a whole story written on her face—her face, which from a distance looked perfect.

*

It’s easy to say that I left my fiancé because he cheated on me. It’s harder to explain the truth. The truth is that I didn’t leave him when I found out. Not even for one night.

I found out about the cheating before we got engaged and I still said yes when he proposed in the park on a day we were meant to be celebrating a job I’d just gotten that morning. Said yes even though I’d told him I was politically opposed to the diamonds he’d convinced me were necessary. Said yes even though he turned our proposal into a joke by making a Bachelor reference and giving me a rose. I am ashamed of all of this.

He hadn’t said one specific thing about me or us during the proposal, and on the long trail walk out of the park I felt robbed of the kind of special declaration I’d hoped a proposal would entail, and, in spite of hating myself for wanting this, hating myself more for fishing for it, I asked him, “Why do you love me? Why do you think we should get married? Really?”

He said he wanted to be with me because I wasn’t annoying or needy. Because I liked beer. Because I was low-maintenance.

I didn’t say anything. A little further down the road he added that he thought I’d make a good mother.

This wasn’t what I hoped he would say. But it was what was being offered. And who was I to want more?

I didn’t leave when he said that the woman he had cheated on me with had told him over the phone that she thought it was unfair that I didn’t want them to be friends anymore, and could they still?

I didn’t leave when he wanted to invite her to our wedding. Or when, after I said she could not come to our wedding, he got frustrated and asked what he was supposed to do when his mother and his friends asked why she wasn’t there.

Reader, I almost married him.

*

Even now I hear the words as shameful: Thirsty. Needy. The worst things a woman can be. Some days I still tell myself to take what is offered, because if it isn’t enough, it is I who wants too much. I am ashamed to be writing about this instead of writing about the whooping cranes, or literal famines, or any of the truer needs of the world.

But what I want to tell you is that I left my fiancé when it was almost too late. And I tell people the story of being cheated on because that story is simple. People know how it goes. But it’s harder to tell the story of how I convinced myself I didn’t need what was necessary to survive. How I convinced myself it was my lack of needs that made me worthy of love.

*

After cocktail hour one night, in the cabin’s kitchen, I told Lindsay about how I’d blown up my life the week before. I told her because I’d just received a voice mail saying I could get a partial refund for my high-necked wedding gown. The refund would be partial because they had already made the base of the dress but had not done any of the beadwork yet. They said the pieces of the dress could still be unstitched and used for something else. I had caught them just in time.

I told Lindsay because she was beautiful and kind and patient and loved good things like birds and I wondered what she would say back to me. What would every good person I knew say to me when I told them that the wedding to which they’d RSVP’d was off and that the life I’d been building for three years was going to be unstitched and repurposed?

Lindsay said it was brave not to do a thing just because everyone expected you to do it.

Jeff was sitting outside in front of the cabin with Warren as Lindsay and I talked, tilting the sighting scope so it pointed toward the moon. The screen door was open and I knew he’d heard me, but he never said anything about my confession.

What he did do was let me drive the boat.

The next day it was just him and me and Lindsay on the water. We were cruising fast and loud. “You drive,” Jeff shouted over the motor. Lindsay grinned and nodded. I had never driven a boat before. “What do I do?” I shouted. Jeff shrugged. I took the wheel. We cruised past small islands, families of pink roseate spoonbills, garbage tankers swarmed by seagulls, fields of grass and wolfberries, and I realized it was not that remarkable for a person to understand what another person needed.

CJ Hauser teaches creative writing at Colgate University. Her novel, Family of Origin, is published by Doubleday.